A Simple Optimization for Time-lagged Independent Component Analysis

Introduction

In October, I joined a research lab which was attempting to utilize Machine Learning for Molecular Dynamics(ML for MD). While I will gloss over the exact details of what we are trying to accomplish and the bigger picture of the work, I may go into more detail in another post later on. In the meantime, you can refer to this post by the professor advising the project. Thus, I will not really answer the question of Why through this post. Instead, I will describe a very basic optimization process which increased the speed our analysis by 10x. This post is really oriented to those curious in what a basic optimization process looks like, show how GPUs can be very useful for scientific research, and a little about the research itself.

Time-lagged Independent Component Analysis

This section will get technical, so if you want to skip the details (most of which won’t be necessary for understanding the optimization process), you can go to the next section.

Time-lagged Independent Component Analysis (TICA) is a linear transformation and dimensionality reduction process [1] which is used in molecular dynamics applications to more clearly capture the kinetic variance[2], or slow motions, of proteins.

To understand how this works, we can start with how proteins are represented. A protein is made up of atoms in certain configurations. These configurations, refered to as degrees of freedom, described the force vectors, rotational motions, and much more for each atom (or set of atoms) in the protein. Thus, each degree of freedom can be represented as a scalar component in an \(n\) dimensional Hilbert Space. A Hilbert Space is a vector space with the inner product operation defined. The Hilbert Space is just the mathematical construction of a vector database, as a simple example. Not all of the degrees of freedom are valuable to describe the slow motions of the protein. There are several dimenstionality reduction schemes that can extract the “important” degrees of freedom, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA). However, TICA is a more reliable method of extracting the slow motions of the protein.

In order to perform this reduction, we require a Hilbert-Schmidt operator, which is a bounded operator \(\kappa: H \rightarrow H\). According to the Hilbert-Schmidt theorem, if \(\kappa\) is a bounded, compact, and self-adjoint operator, then there is a sequence of non-zero real eigenvalues \(\lambda_i = 1,\cdots,N\) with \(N\) being the rank of \(\kappa\) such that \(\lambda_i\) is monotonically non-increasing. The proof that \(\kappa\) is a bounded, compact, and self-adjoint operator is omitted but can be found in [1]. Furthermore, if each eigenvalue of \(\kappa\) is repeated in the sequence according to its multiplicity, then there exists an orthonormal set \(\varphi_i, i=1,\cdots,N\) of corresponding eigenfunctions in the form

\[\kappa \varphi_i = \lambda_i \varphi_i \text{ for } i = 1,\cdots,N\]Thus, there exists an eigenvalue decomposition

\[\kappa = \sum_{i=1}^{\infty} \lambda_i \langle \cdot, \varphi_i \rangle u \varphi_i\]“The objective of TICA is to yield components that are uncoorelated and also maximize the time-autocorrelation function under time-lag \(\tau\).” [1] Thus, we utilize a time-lagged coorelation matrix \(\mathbf{C} (\tau)\) with elements

\[c_{ij} (\tau) = \langle x_i (t), x_j(t + \tau) \rangle_t\]Then, one can solve the generalized eigenvalue problem

\[\mathbf{C} (\tau) \mathbf{u}_i = \mathbf{C} (0) \lambda_i (\tau) \mathbf{u}_i\]The resultant \(\mathbf{u}_i\) is the independent component directions which are linear approximations to reaction coordinates of the system. The components have maximal auto-correlation measured by the \(\lambda_i\). We use this reduction for a whole host of purposes, such as plotting the protein by its first two TICA components to understand how our model matches against the ground truth (each dot is frame, which will be explained later):

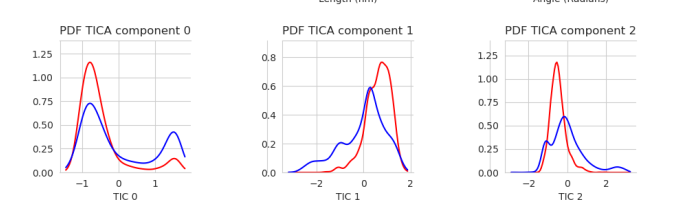

We can also use a kernel density estimation (KDE) to show the probability density function (PDF) of the points for each component:

Performing this operation is key to analyzing the results of our model. We want to make sure we are getting the best information by varying the possible inputs to the TICA model. Let’s take a look at how we generate a TICA model in the code.

The TICA Analysis Code

In order to do our analysis, we used the Deeptime Library [1], which is a python library for machine learning dynamic from time series data. This library has a component that focuses on the TICA reduction which we utilize to do the reduction. You can look at the code on your own but I will have relevant snippets throughout the post. In molecular dynamics, information about proteins such as atom type and location or bonds is stored in a PDB or HDF5 file. This is the state of the protein at a single timestep in an MD simulation (refered to as a frame). For each frame, using traditional MD, the next state of the protein is calculated and a new frame is generated. This creates a list of frames, which is called a trajectory, and appears as a “movie” of a protein which can be seen here:

(Still image of the protein, i.e. a single frame. White is Hydrogen atoms, red is Oxygen, blue is Nitrogen, and the beige color is Carbon. Also, the purple and green dots in the distance are water ions to create polarity for the simulation)

(The visualization is from a UCSF tool called ChimeraX)

We store this information in wrappers around the MDTraj library which helps us store and operate on the frames and the proteins.

@dataclass

class NativeTraj:

trajectory: mdtraj.Trajectory

forces: NDArray

path: str

def stride(self, stride: int):

return NativeTraj(self.trajectory[::stride], self.forces[::stride], self.path)

@dataclass

class NativeTrajPathNumpy:

numpy_file: str

pdb_top_path: str

@dataclass

class NativeTrajPathH5:

h5_path: str

pdb_top_path: str

NativeTrajPath = NativeTrajPathH5 | NativeTrajPathNumpy

When we need to generate a TICA model (aka it hasn’t been created already and cached), we call the generate_tica_model function

def generate_tica_model(native_trajs: list[NativeTrajPath]) -> tuple[TicaModel, list[numpy.typing.NDArray]]:

native_bond_lens: list[numpy.typing.NDArray] = calc_atom_distances(native_trajs)

#lag time is for lag correlation matrix

#like the covariance matrix but if one variable was offset by a lag time = Δt

#https://rmcgibbo-msmbuilder.readthedocs.io/en/latest/theory/tICA.html

estimator = deeptime.decomposition.TICA(lagtime=LAGTIME, dim=None)

for i, traj in enumerate(native_bond_lens):

print(f"done {i}/{len(native_bond_lens)}")

for X, Y in deeptime.util.data.timeshifted_split(traj, lagtime=LAGTIME, chunksize=200):

estimator.partial_fit((X, Y))

model = estimator.fetch_model()

native_projected_datas = [model.transform(x) for x in native_bond_lens]

kde_2d = scipy.stats.gaussian_kde(numpy.concatenate(native_projected_datas)[:, :2].transpose())

tica_data = numpy.concatenate(native_projected_datas)

xmin, xmax = numpy.min(tica_data[:, 0]), numpy.max(tica_data[:, 0])

ymin, ymax = numpy.min(tica_data[:, 1]), numpy.max(tica_data[:, 1])

return TicaModel(model,

kde_2d,

xmin,

xmax,

ymin,

ymax), native_projected_datas

It has a list of paths which contains trajectories. [3]. We then create the TICA estimator from deeptime.

estimator = deeptime.decomposition.TICA(lagtime=LAGTIME, dim=None)

This estimator is used for TICA analysis and we will see the interal execution soon. Then we go through each trajectory

for i, traj in enumerate(native_bond_lens):

print(f"done {i}/{len(native_bond_lens)}")

for X, Y in deeptime.util.data.timeshifted_split(traj, lagtime=LAGTIME, chunksize=200):

estimator.partial_fit((X, Y))

After the loop finishes partial-fitting on each trajectory, the rest of generate_tica_model constructs a final TICA model, projects each trajectory into that model’s reduced space, and prepares some post-processing objects.

model = estimator.fetch_model()

Once all frames from all trajectories have been used to fit the TICA estimator (via the iterative partial_fit calls), fetch_model() creates a finalized TICA model. Internally, this step will compute the TICA components (eigenvalues and eigenvectors) from the accumulated covariance and time-lagged covariance estimates.

native_projected_datas = [model.transform(x) for x in native_bond_lens]

After we have our final TICA model, we transform each original trajectory (in this case, the bond-length arrays in native_bond_lens) into the new TICA feature space. TICA tries to identify the slow collective coordinates in the data, so each x, which is an \(N \times d\) matrix of features (e.g. bond lengths over \(N\) frames), gets mapped to the lower-dimensional set of TICA coordinates resulting in the list of arrays of size \(N \times m\) where \(m\) is the number of dimensions after the TICA reduction.

While I was running this process over many iterations, the code was very slow and it was frustrating me. Thus, we shall see what I did to address this.

Benchmarking and Optimization Process

One component of the research was determining what combinations of lag time, trajectories, strides, and model types create the best TICA model.

def main():

for i in range(len(models)):

for s in strides:

for lag_time in lagtimes:

for native_folder in native_folders:

try:

create_tica_model(get_native_paths(native_folder), os.path.basename(native_folder), models[i], i, lag_time, s)

except:

print("Could not create model with parameters: " + str(lag_time) + str(models[i]))

(Note: create_tica_model is a just a wrapper on generate_tica_model)

This means I would generate up to 300 TICA models. This generation process would take a long time, and I wanted to see if it was possible to speed up this process. This is where I will introduce Amhdal’s Law. You can refer to the “official” definition from Wikipedia, but I have heard two main “lessons” from Amhdal’s Law. First, optimize the costly things first. Second, the benefit of parallelism is bottlenecked by the cost of re-combining the data. We will focus on the first example, since I was looking for the best area to focus on while increasing the speed. Thus, I used the Python profile tool which gave me insight into which functions were taking the most time. To profile the program, I ran

python3 -m cProfile -o ./profiling/tmp.prof create_tica_models.py

which runs cProfile on the program create_tica_models.py with the output in a tmp.prof file. Then, using the little script below, we can view the results in a text file:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import pstats

stats = pstats.Stats('tmp.prof')

stats.strip_dirs().sort_stats('tottime').print_stats()

I am sorting by ‘tottime’ which is the total time that a function runs not including the time when that function calls another function. Thus, we see where the computation bottleneck exists. Here were the results:

12834251 function calls (12757031 primitive calls) in 36.079 seconds

Ordered by: internal time

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

520 14.686 0.028 14.686 0.028 _moments.py:378(_M2_dense)

2 4.480 2.240 4.481 2.241 _eigen.py:82(spd_eig)

130000 2.460 0.000 4.862 0.000 unitcell.py:104(box_vectors_to_lengths_and_angles)

For each function, the profiler provides the number of calls (ncalls), tottime (total time in the function), the total time per call, cumtime (the cumulative time which is the total time + the time of all subfuctions), and the cumulative time per call to help understand which functions take up the most time. The obvious bottleneck, which takes one-third of all the processing time, is the function _M2_dense in _moments.py (line 378). A little bit a grepping leads and we get the our culprit: _moments.py

def _M2_dense(X, Y, weights=None, diag_only=False):

""" 2nd moment matrix using dense matrix computations.

This function is encapsulated such that we can make easy modifications of the basic algorithms

"""

if weights is not None:

if diag_only:

return np.sum(weights[:, None] * X * Y, axis=0)

else:

return np.dot((weights[:, None] * X).T, Y)

else:

if diag_only:

return np.sum(X * Y, axis=0)

else:

return np.dot(X.T, Y)

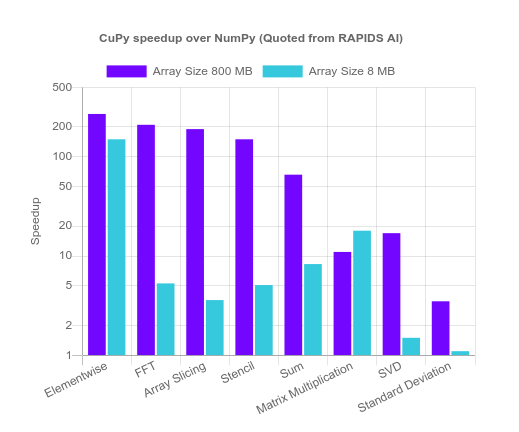

Since this function consists of lots of summations and dot products, they are bottlenecked by the capabilities of the CPU. They are both parallelizable functions. Thus, I used CuPy, an NVIDIA tool to for GPU-accelerated programming in Python without having to write CUDA itself. According to RAPIDS AI, the CuPy version of summation can reach speedups between 8.3 to 66x.

First, once installed, we import CuPy to use:

import cupy as cp

To convert the function, we first have to convert the arrays from Numpy to Cupy arrays:

X = cp.asarray(X)

Y = cp.asarray(Y)

We also have to do that with the weights array, but we would only want to do that if the weights were not None. Additionally, we want to do element-wise multiplication between the weighted array and X. Thus we have

if weights is not None:

weights = cp.asarray(weights) # Convert weights to CuPy array

weighted_X = weights[:, None] * X # Element-wise multiplication with broadcasting

The last adjustment is to do the summation and dot product. The sum is basically the same but the dot product will use the @ notation. Thus, we have

if diag_only:

return cp.sum(weighted_X * Y, axis=0)

else:

return weighted_X.T @ Y

or for unweighted

if diag_only:

return cp.sum(X * Y, axis=0)

else:

return X.T @ Y

The final result is as follows:

def _M2_dense_gpu(X, Y, weights=None, diag_only=False):

"""2nd moment matrix using CuPy for GPU-accelerated computations."""

X = cp.asarray(X)

Y = cp.asarray(Y)

if weights is not None:

weights = cp.asarray(weights) # Convert weights to CuPy array

weighted_X = weights[:, None] * X # Element-wise multiplication with broadcasting

if diag_only:

return cp.sum(weighted_X * Y, axis=0)

else:

return weighted_X.T @ Y

else:

if diag_only:

return cp.sum(X * Y, axis=0)

else:

return X.T @ Y

Doing some comparions between the two functions, where on the left is time _M2_dense takes and the right is _M2_dense_gpu, on realistic workloads, the results are as follows:

1.269303560256958,0.24415206909179688)

(1.2439026832580566,0.08305549621582031)

(1.3065624237060547,0.08765721321105957)

(1.2483961582183838,0.08765959739685059)

(1.215346336364746,0.07702016830444336)

(1.5265223979949951,0.07275581359863281)

(1.2115592956542969,0.08763337135314941)

(1.173168659210205,0.07700920104980469)

(1.5756299495697021,0.07213211059570312)

(1.623317003250122,0.08763456344604492)

(1.2237708568572998,0.07703423500061035)

(1.326847791671753,0.07218623161315918)

(1.3135099411010742,0.08763575553894043)

(1.2472302913665771,0.07956981658935547)

(1.3129246234893799,0.07642722129821777)

(1.1265039443969727,0.07582569122314453)

(1.4395310878753662,0.07347655296325684)

(1.175112247467041,0.08766651153564453)

(1.0875110626220703,0.0770425796508789)

(1.5078003406524658,0.08767151832580566)

(1.2399332523345947,0.08774685859680176)

(1.2756452560424805,0.08507490158081055)

(1.12247633934021,0.08764076232910156)

(1.1715912818908691,0.0876314640045166)

(1.357269525527954,0.08765220642089844)

(1.218057632446289,0.08767080307006836)

(1.2859292030334473,0.08652567863464355)

(1.2058954238891602,0.08604216575622559)

(1.1828789710998535,0.07704401016235352)

(1.1473486423492432,0.08763647079467773)

Average Reg: 1.2787158727645873

Average Cuda: 0.0877303679784139

Speedup: 14.575521592240626

A 14x speedup on the _M2_dense function. Making the switch in the source code and restarting the profiler, indeed, the function is no longer a bottleneck:

13368778 function calls (13288544 primitive calls) in 18.579 seconds

Ordered by: internal time

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

130000 2.831 0.000 5.656 0.000 unitcell.py:104(box_vectors_to_lengths_and_angles)

2 1.472 0.736 1.473 0.737 _eigen.py:82(spd_eig)

2 1.295 0.648 1.295 0.648 _decomp.py:283(eigh)

4 0.868 0.217 0.868 0.217 {method 'read' of 'h5py._selector.Reader' objects}

390438 0.671 0.000 0.671 0.000 {method 'reduce' of 'numpy.ufunc' objects}

Thus, I cut between a third and a half of the processing time. This made the process of creating new experiments much faster without that much hard work required.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: